After weeks of pondering our destination, making plans, gathering our gear, and then adjusting our schedule to roll with mother nature’s program, we are at last on the trail. Hiking uphill. Yes, that’s how it starts, uphill through golden hills of wild grasses.

I had originally envisioned a trek through evergreen pines along the length of Piedra Blanca Trail. My friend and I had hiked there Thanksgiving weekend five years ago and the scenery was just epic. But even as I was conceiving of a shuttle hike from Reyes Creek Campground to the Piedra Blanca Trailhead, I was remembering every time I’ve hiked the trail I’ve seen people.

Thinking we might prefer some place less traveled, I began considering where else we could go without adding extra miles or days; the Piedra Blanca Trip would be 18.5 miles over three days. Then it dawned on me, one of our first backpacking trips together was along Pothole Trail to Cove Camp, about 17 miles over three days.

Nevertheless, I remained on the fence, that is until the weather changed. With my friend’s kids out of town for Thanksgiving, it made sense to start Thursday for a 3-day backpacking trip. We would have Thanksgiving with her kids on Wednesday, hike three days, and have Sunday at home for relaxing.

But nature has her own plans. With a pending storm arriving Thanksgiving Day and predictions of snow at the higher elevations, plus a second storm arriving on Saturday, there was a possibility Highway 33 could be closed and significant portions of Piedra Blanca Trail might be covered in snow, the latter not necessarily a bad thing. Rather than wait until the very last minute, we settled on the Agua Blanca, shifting our timeline to leave on Friday, after the first storm, and return on Sunday.

On Wednesday, I met with a friend who has property back by Lake Piru to borrow his keys and save ourselves about four miles of road walking both ways.

Currently, access to the Pothole Trailhead and points beyond is restricted by a series of gates and a parking fee. The area around Lake Piru is owned and managed by United Water Conservation District. This time of year one can drive in as far as the lower lot and park and then continue on foot to the trailhead.

The good news is all of that is changing, hopefully this year. The existing gates will be removed or kept open, with a new locked gate installed just past the trailhead. There will be a new parking area with no fees. The new gate past the trailhead will still require keys as before, but access to the Pothole Trail will be open, and the distance to Agua Blanca Trail, Ellis Apiary, and Piru Gorge will effectively become shorter. This is also great news for the Condor Trail, the 420-mile long through hike route which either begins or ends at Pothole Trail depending on how you hike it, will now be unburdened of 3-5 miles of tedious road walking.

*

Anyway, yes, Friday morning, we are now on the trail. The sun is out and it’s good to be feeling its warmth after two days of rain. The hillsides are covered with wild grasses and dotted with yerba santa and purple sage. Lining the trail like diaphanous angels is something reminiscent of dove weed. Our last hike along this trail was in 2013, when I was section hiking the Condor Trail for a series of articles.

As we continue up the trail we start seeing bear scat loaded with hollyleaf cherry and begin to wonder if we’ll encounter a stand of cherry bushes somewhere along the trail. There’s something reassuring to me about bears using the trails, and the frequency of scat here reminds me of Santa Cruz Trail in the San Rafael Mountains. There’s a section of the 40-mile wall that’s a veritable cherry grove and during a particular hike I did one September there was an amazing amount of bear scat along the trail with nothing but hollyleaf cherry pits in it.

From the trailhead, Pothole Trail offers a hearty uphill gain of roughly 2,100 feet, more than enough it would seem to help burn off Thanksgiving dinner and associated holiday slothfulness.

As we crest the first rise, we arrive at a small stand of California black walnuts recovering from the 2007 Ranch Fire. The tree is more common in Ventura County and further south. In fact, the only place I’ve seen it so far in Santa Barbara County is along the access road to Gibraltar Dam.

Sugar Bush

The next plant to command our attention is Sugar Bush or is it Lemonade Berry? We both recall taco-shaped leaves being indicative of Sugar Bush, but after looking at the flower buds, we start to second guess ourselves. Both plants are in the genus Rhus, which is part of the Cashew or Sumac family, Anacardiaceae. The family includes Cashews and Pistachios, as well as Laurel Sumac and Poison Oak, which we’ll meet later on the trail.

Lemonade Berry, however has rounder, flatter, and more leathery leaves, while Sugar Bush, like the example here, has more curved-shaped leaves that end in a point. Lemonade Berry also prefers the coast, while Sugar Bush prefers being inland. Sugar Bush flowers between March and May.

Blue Point, in the foreground right

As we continue along the wide ridge, to the north Blue Point comes into view. The point is said to be named for its bands of bluish-grey rock. Near its base, to the east, is the now closed Blue Point Campground. The campground was closed in 2000 to help protect the Arroyo Toad and other endangered species. The mountain’s name calls to mind another Blue Point, this one at the top of Fir Canyon, in the San Rafael Mountains. In his journal, Ranger Edgar Davison referred to the prominent outcrop of Serpentine as Blue Point. He referred to the canyon as Blue Canyon, and later renamed it Fir Canyon, which is helpful since there is also a Blue Canyon on the backside of the Santa Ynez Mountains.

“Blue Point” near the top of Fir Canyon in the San Rafael Mountains

After still more uphill, we arrive at the first lupine and the base of yet another climb. Here, to the left we can see the marked trail veering away from the ridgeline we’d been following. Thus far, we’d been avoiding the official trail, reluctant to follow its self-imposed trajectory through the weeds. The route, marked with flexible, brown carsonite signs, sort of parallels the use trail everyone seems to favor.

So I thought we should at least give the official route a try since it looks like it might break up some of the climb. Bad idea. The trail is brushier than the open ridge, the tread is torn up from horse traffic, and the real clincher for me is the bears don’t use it.

The trail then fortunately rejoins the more open ridge as we climb yet another hill. This one ablaze with buckwheat, its rust-colored dry flower heads radiant on the landscape. And then suddenly I notice a patch of snow on the ground, and then another, something I was not expecting at this low of an elevation.

Yerba Santa and Buckwheat

The trail then chugs up yet another hill. Here, yerba santa is growing amongst the buckwheat. Both plants cleansed of their dust by the recent rain are now beaming vibrant colors on the landscape, with the reds of the buckwheat offset by the pale greens of the yerba santa. Hiking through this grove of color I feel the elements beginning to work on me, peeling away layers of daily city life, while the scenery, with it patches of snow, becomes more magical and lucid, like something out of an Alphonse Mucha print

In the distance, Cobblestone Mountain comes into view, its snow-covered summit obscured in the clouds like some local version of Mount Everest. The mountain reaches 6,733 feet, and stands watch over Agua Blanca Creek. Along its top I can see pines covered in snow, like white-flocked Christmas trees.

Cobblestone Mountain is seen in the distance

Bobcat Tracks

We then reach the wilderness sign, which also marks the end of our uphill climb. The entire backside of the ridge is covered in snow. Along the trail, as if welcoming us into the Sespe Wilderness, is a set of fresh bobcat tracks coming up the trail.

The trail cuts across the backside of the ridge we’d been following and then heads down the ridgeline separating the Pothole drainage from the next creek over that also flows into the Agua Blanca. The trail has some brushy sections as it descends, but generally improves as it starts to level out; here we catch our first glimpse of the almost iconic Pothole.

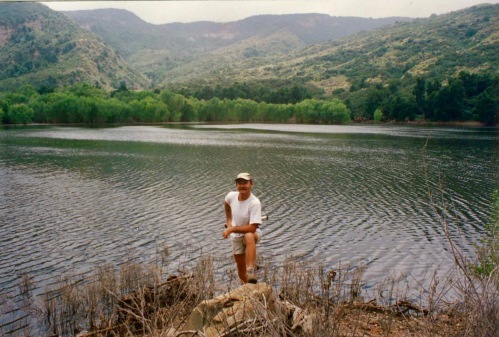

The Pothole

The trail then wraps around the ridge, doubling-back for its final descent into the canyon, offering views of Devil’s Gateway, Pothole Spring, Devil’s Potrero, and the Pothole. With the sun now breaking through the clouds, illuminating the basin in a glorious display of light, I start running down the trail to catch photos of the Pothole before the sun disappears.

Pothole Spring is seen from the trail

Cottonwoods in the Pothole seen from the trail

At some point in the not too distant past, there was by some accounts an earthquake and/or a large landslide that piled debris across the canyon helping to form the three separate basins was see today: The Pothole, Devil’s Potrero, and Pothole Spring. A similar phenomenon is said to have created Zaca Lake in the San Rafael Mountains, which was formed by a landslide that deposited debris across that canyon. Yes, another reference to the San Rafael Mountains.

Back when I first wrote about Pothole Trail a reader sent me a picture of the Pothole filled with water from the early 1990s; he said the water was around 15 feet deep and during one of his visits he found the remains of a rowboat. I’ve often wondered if the boat was still there.

The Pothole c. 1994 – image courtesy Hank Weishaar

The Pothole c. 1994 – image courtesy Hank Weishaar

Into the Pothole

Where the trail meets the canyon floor, at the edge of Devil’s Potrero, we pause for lunch under a large oak. Originally, I had thought of pushing all the way to Cove Camp on the first day, about 8.5 miles, but my friend preferred we aim for Log Cabin Camp, about 6 miles, to break up the hike. This also meant we would have time to explore the Pothole. In my haste of changing up plans last minute I didn’t take the time to research if there was even a trail into the Pothole or check Google Earth to scout something out. On the hike in I didn’t see any obvious routes.

Instead I have to rely on my intuition, imagining if there wasn’t an informal route there would at least be a game trail as animals would likely want to access or traverse the basin. Feeling drawn to the oak woodland west of the main trail, I begin following an animal trail through the grove of oaks, which my friend observes would also make an ideal place for a gathering of Druids.

Following the most prominent game trail along the edge of the chaparral and trying different spur trails that look like they would cut north towards the Pothole, I eventually find a trail that climbs up a low rise and looks promising. The trail crests out of Devil’s Potrero, weaving through the chaparral, and then begins to descend, taking on more definition as it continues. We’re now clearly on some kind of use trail. The trail carries us to the edge of the Pothole, arriving at a dense stand of cottonwoods, golden with the colors of autumn. We continue on the use trail as it skirts east around the cottonwoods and out into the open part of the basin.

Cottonwoods in the Pothole

In the Pothole

My friend pauses here to take in the sights and sounds of the nearby cottonwoods, while I cut out across the open basin, soaking in the experience, and ostensibly scanning the edges for that boat.

Completing my circuit around the Pothole and not finding any boats, I return to where I left my friend only I can’t see her. It isn’t until I arrive where she was sitting I discover she is now lying down, lulled into a nap by the sound of the gentle breeze playing through the cottonwoods.

Cottonwoods growing in the Pothole

We return to our packs and resume our trek towards the Agua Blanca. The trail skirts the edge of Devil’s Potrero, and then continues down a small side canyon, passing a barbed wire fence and a sign that once said no trespassing. The trail then arrives at the edge of Pothole Spring, where there’s an open, marshy stand of water, framed by tules and willow. Overlooking the spring, on the top of a rise, is the old Whitaker homestead. William Whitaker homesteaded here in the late 1800s, receiving a patent on the land in 1891. On the west side of the cabin is a collection of farm implements that were packed in by mule.

Pothole Spring

Whitaker Homestead

Farm equipment is seen outside the Whitaker Homestead

Continuing around to the back side of the cabin, I trace the western edge of Pothole Spring and spot a bear trail cutting through the reeds, heading off to wherever it is a bear might want to go. I think of following it, but opt instead to press onto Log Cabin Camp.

Continuing past the homestead, Pothole Trail descends through oak woodland before transitioning down into a creek. The flowing creek, lush with alder trees and ferns, now saturated from the recent rains feels almost like a Pacific Northwest rain forest. Lion’s mane is seen growing on one of the downed oaks and I keep looking to see if there are any banana slugs along the trail.

The trail then arrives at Agua Blanca Creek, just upstream from the Devil’s Gateway. The Agua Blanca is flowing with just a hint of tannin from the recent rain. Across the creek is a trail sign which points the way to Log Cabin Camp. We then pass a second trail sign, which marks where Agua Blanca Trail bypasses Devil’s Gateway.

We arrive at Log Cabin Camp, just as we had done six years ago. The camp seems like it’s seen more use since our last visit. We set up camp, gather water, and settle into a hearty meal of backcountry tacos, with tri-tip, rice, and beans, garnished with cheese, cilantro, and onions.

After dinner, with impressively clear skies, we take in some stargazing, accompanied by the call of a Great Horned Owl, before settling in for the night.

Onward to Cove

In the morning, we opt for a simple breakfast so we can get on the trail early. Our plan is to get to Cove and set up camp before the predicted afternoon rain starts so we’ll have a dry place to work with. However, as I head down to the creek to filter some water, something tells me it would be better to stay put; we already have a tent here that’s dry. If we instead day hike to Cove we will be far less anxious about beating the rain and also have less miles to cover on the hike out, which would support a more leisurely trip overall. The downside in my mind is Cove Camp is a much nicer site than Log Cabin Camp, and we also run the risk of not getting to visit the Big Narrows. After a reasonable amount of hand wringing and internal debate, I decide to go with the day hike plan.

As we hit the trial, we are greeted by a hawk, sounding somewhat distressed, only to then see and hear a second hawk. The two continue up the canyon, leading the way. The trail is overgrown in places, and it looks like the bears are the ones using the trail the most.

We quickly arrive at Hollister. The site is shown on some maps as a camp, but in reality it’s a benchmark. However, instead of just a metal something, it’s a large almost cube-shaped stone with the letters “B” and “M” carved into it. On top is the benchmark.

Hollister

From here, the trail becomes more overgrown, requiring more route-finding and deciphering the mish-mash of flagging, which is a little like listening to several different people debate where they think the trail ought to go, or worse still the route they so proudly took.

Eventually the trail returns down to the creek and more or less disappears. It’s here that the rain starts and any regrets I had about camping at Log Cabin Camp a second night begin to leave me.

The trail then picks up again, and as it continues it becomes what could be described as a true wilderness adventure — overgrown, brushy, downed trees, bear sign and scat, and plenty of poison oak crowding in. In addition to keeping one’s trail skills fresh, it also puts to test one’s ability to differentiate between poison oak and basketry bush aka skunk brush, both of which grow in abundance along the trail and can have a similar appearance

About halfway between Hollister and Cove we pause for a snack to bring up our energy and stave off the cold from the increasingly steady rain. Getting up from our snack we spot a hollyleaf cherry bush laden with ripe fruit, which we sample. Then looking around we realize we are surrounded by cherry bushes and the myriad of side trails I’d been seeing earlier are actually from the bears gorging themselves on this veritable grove of cherries. Perhaps this was the larder of cherries the bears had been eating and later depositing along the trail. A little further up we even find fresh bear tracks in the creek bed.

Hollyleaf Cherry

Bear tracks Agua Blanca Creek

Agua Blanca Creek

The canyon then starts to narrow, becoming even more scenic. And in spite of the rain, it seems like we’re having a generally good time taking in the scenery and feeling the immersiveness of a trail that not many people seem to visit.

As the canyon opens back up, trail conditions begin to improve. But at one point, as I watch my friend ninja her way around yet another patch of poison oak, she just loses it. After hiking in the rain, pushing through brush, route finding, and dealing with poison oak she’s had enough. “I’m so tired of freaking poison oak” or words to that effect, she shouts as she has a mini meltdown.

Being way more sensitive than me to the effects of poison oak I’m sympathetic to her plight, and at the same time I have a strong suspicion we’re almost at Cove Camp. I’ve noticed sometimes in the backcountry just as we near our destination our mind begins to play tricks on us, our fatigue tells us it’s pointless to go on, when in reality we’re almost there.

I share with her a story about a trip I did once looking for some cave paintings with a friend along another overgrown creek in the Sespe Wilderness. It had been a workout making our way up the creek, scrambling over fallen trees and pushing through brambly regrowth from the Day Fire, when my friend decided we had either gone too far or had faulty information, and either way was turning back. And while I felt his fatigue, I had a funny suspicion, based on the intel we had, the site was still up ahead and so I pressed on alone. Ten minutes later I arrived at the site, found the cave paintings, and then raced back down the creek to catch him so he wouldn’t miss out.

With my friend now less upset and busy pondering the merit of my story, we continue up the trail, which now uncharacteristically pulls away from the creek, riding above it, which suggests to me we are in fact nearing Cove Camp. The trail then rounds a corner and stretched out beneath us, under the oaks and sycamore, is Cove Camp. A northern flicker calls out to us as we descend down to the site.

Cove Camp

The camp features a double wide ice can stove and a fire ring; nearby is a sign for the camp wedged between two trees. The camp is situated in a large flat and up canyon, near the camp, is a regular ice can stove, and then past that another double wide one. I’d forgotten the Agua Blanca was a storehouse of relic ice can stoves, so far this day I’ve seen seven. (Log Cabin Camp has four ice can stoves, two near the stone fire ring and pedestal stove at the main camp, a third one just east of the camp under the canopy of oaks, and the fourth in the relatively open area overlooking the creek.)

Taking shelter under an overhanging ledge we have lunch gazing out across the camp, which was more inviting six years ago when it wasn’t raining. We opt to let go of hiking the Big Narrows, which would add another two miles roundtrip in the rain, and content ourselves with having reached Cove and reminiscing about past hikes.

Cove Camp

Under still leaden skies, as the rain increases, we retrace our route back to our camp, trying some alternate sections, re-route-refinding in places, and criss-crossing the creek back downstream to Log Cabin Camp. At one point, while crossing the creek yet another time, looking for our route in reverse, I reach my limit and wonder just how much more of this we still have left. Feeling as if we’re going in circles, in these now grey woods, I start to think I might just find a tobacco pouch on the ground left by dwarves from the Blue Mountains. And then just like that, past this last crossing, the trail climbs away from the creek and we arrive at the outskirts of camp.

Agua Blanca Creek

Still raining, my friend dries out the interior of our tent from some leaks, while I make dinner in the rain. In anticipation of the inclement weather I’ve selected something that would be easy to make and clean up in the rain, Mac and Cheese.

Instead of bringing my lightweight Big Agnes tent, which comes in around three pounds, I deliberately brought my roomier Big 5 World Famous Sports tent, which weighs 4.5 pounds. Although heavier, the tent is large enough that we can stow all our gear inside, instead of having to leave most of it outside, under the vestibule, with the narrower Big Agnes tent.

After dinner we settle in early for a cozy night of reading while the rain continues, content in the knowledge that all of our gear is dry with us inside the tent.

In the morning we are awakened in the predawn hours by a Great Horned Owl, followed a little later by a dawn chorus of mostly woodpeckers and stellar jays that goes on for some time, a strong indication to me the rain is indeed over.

We spend part of the morning drying out from the day before, while enjoying a hearty breakfast of scrambled eggs with rice and beans.

As we hit the trail, the sun is still struggling to break through the clouds. We drop our packs at the juncture with Pothole Trail and make our way down to Devil’s Gateway for a quick visit just as the sun breaks out of the clouds, illuminating the entrance to the gateway and the nearby golden leaves of the Cottonwoods and California Black Walnut.

Devil’s Gateway

On the hike back out we again savor the great scenery. The snow that was on the trail on our hike in is now completely gone, and the pines on Cobblestone Mountain are now once again dark green, while the mountain remains shrouded in a blanket of white. Nearing the end of our climb out, we pause at a large manzanita bush that is laden with ripe fruit and enjoy a quick snack before making the long descent back down to the trailhead. We arrive at our car just as the sun is setting, feeling like we’ve maximized our time outdoors to the fullest.

Manzanita

Leave a comment