On Christmas Eve, 1846, Lieutenant Colonel John C. Frémont made his historic ascent along what is now known as Fremont Ridge during the Mexican-American War. Frémont and his men were en route to capture Santa Barbara, which was then still part of Mexico.

Starting from East Camino Cielo one can make a short day hike along a portion of Frémont’s route. The hike is about three miles round trip and includes some sweeping views of the San Rafael Mountains and Santa Ynez Valley.

To get to the trailhead from Santa Barbara, take State Route 154 to the top of the Santa Ynez Mountains. Turn right onto East Camino Cielo Road, and continue about two miles and look for an unpaved access road on the left with a metal gate that leads down the backside of the mountains. You’ll know if you’ve gone too far as a mile later you’ll arrive at the intersection with Painted Cave Road. Parking is available in the pullouts alongside the road near the gate.

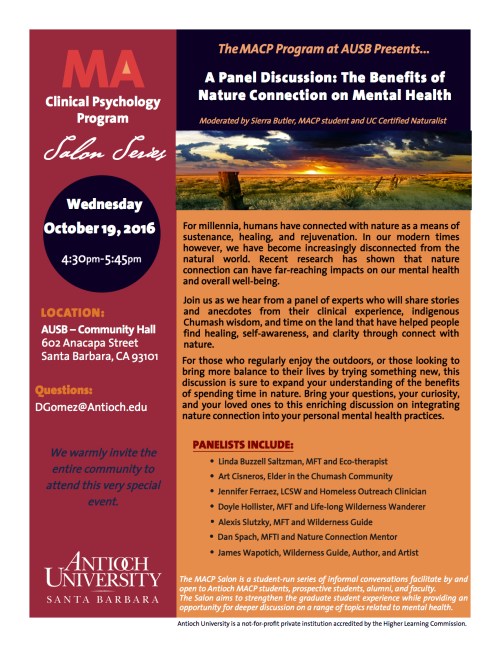

The San Rafael Mountains are seen from Fremont Ridge Trail

From the trailhead, the access road, also known as Fremont Ridge Trail, descends gradually through a mix of coast live oak and madrone. The views then open up back towards the top of the mountains and a stand of Coulter pines, a number of which are suffering from the drought.

As the road continues it settles in on the ridge and here, the views open up dramatically. Across Los Laureles Canyon one can see State Route 154, the Cold Spring arch bridge, Broadcast Peak, and the sweep of the Santa Ynez Valley, including what’s left of Lake Cachuma. Continuing in an arc, the panorama takes in the San Rafael Mountains stretching from Lookout Mountain to San Rafael Mountain.

Past this vista point, the road descends more rapidly downhill, eventually leveling out and arriving at a set of power lines. Here, the route Frémont used continues through private property and is closed to the public.

The steepness of the route in places and the healthy stands of chaparral on both sides of the road give some sense of what the climb might’ve been like for Frémont’s forces as they trudged uphill with their horses and artillery.

John Charles Frémont was born in Savannah, Georgia in 1813. In 1838, he joined U.S. Army Corps of Topographic Engineers, becoming a second lieutenant. Through the Corps he participated in a number of survey expeditions through the western territories the US had acquired as part of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase.

In 1841, he married Jessie Benton, whose father was Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri. An influential Senator, Benton was a proponent of the expansionist movement and saw to it that Frémont was put in charge of a number of expeditions to survey and help open up the American West.

During his first expedition in 1842, Frémont met Kit Carson, who he enlisted as a guide. Frémont surveyed the area between the Missouri River and Rocky Mountains, and his subsequent survey report, which was published in various newspapers, garnered him celebrity status.

His second expedition in 1843, surveyed what would become the second half of the Oregon Trail. From Oregon, he continued south into Alta California, making a loop back through the Great Basin.

His third expedition west in 1845, was likely a pretense used by President Polk to send Frémont to California to be available should war break out with Mexico. In April 1846, the Mexican-American War began.

In July 1846, the US Navy captured Monterey, California. Commodore Robert F. Stockton was put in charge of land operations and appointed Frémont in charge of the California Battalion, which Frémont had helped organize with men from his survey expedition, volunteers from the short-lived Bear Flag Republic, and a group of Indians from Oregon.

Towards the end of 1846, Frémont left Monterey with 478 men and traveled south, bringing with them several wheeled cannons. On December 18, they arrived at William Dana’s adobe in Nipomo.

From there, they continued south, crossing the Santa Maria River and following it upstream to Sisquoc River, where they camped. The next day, they covered little ground and camped in Foxen Canyon, where they were visited by Benjamin Foxen, who owned the land. The site today is marked with a plaque along Foxen Canyon Road.

Over the years, It has been suggested that Frémont was originally planning to cross the Santa Ynez Mountains at Gaviota Pass, but was tipped off by Foxen that an armed ambush awaited him there. Foxen is said to have suggested that Frémont cross near San Marcos Pass instead and with his son guided them along the route.

However, local historian Walker Tompkins has pointed out there are several problems with this story. First, there wasn’t a viable route through Gaviota for wheeled vehicles until 1859. Second, the soldiers and most of the able bodied men from Santa Barbara had already gone to Los Angeles to make a stand there. And third, there is no written record of the story in either Frémont’s journal or those of the men with him.

The most common route in those days from the Santa Ynez Valley to the coast was along El Camino Real, which connected the Missions, and led over the mountains at Refugio Pass, where Refugio Road is now.

From Foxen Canyon, Frémont and his men continued to Alamo Pintado Creek, near where Los Olivos and Ballard are today. On December 21, Frémont decided that instead of following El Camino Real, it would be quicker and safer to follow an old Chumash trail over the mountains near San Marcos Pass, along what is now known as Fremont Ridge.

On December 22, they camped along the Santa Ynez River, near where Cachuma Dam is now, before continuing upstream. The next day, they camped along the river, near where Frémont Campground is now located on Paradise Road.

On December 24, they began their march up the eastern ridge of Los Laureles Canyon. Frémont’s advanced scouts made it to the top by noon and continued west towards Kinevan Canyon where they camped. The rest of the battalion, slowed by the heavy cannons, didn’t make it to the top until just after nightfall and likely camped near Laurel Springs.

On Christmas Day, it started raining. Frémont and his men spent the entire day and long into the night, making their way in the rain down the front side of the mountains to the foothills behind Goleta, where his advanced scouts had located a place to camp.

There, they spent the next several days drying out, recuperating, and recovering gear and artillery that had been abandoned during the descent. The ordeal cost Frémont close to 120 horses and mules; miraculously no human lives were lost.

On December 27, Frémont resumed his march towards Santa Barbara. The next day, with Santa Barbara undefended, Frémont’s forces took the Presidio without incident and raised the American flag.

On January 3, 1847, Frémont’s forces left Santa Barbara and continued to Los Angeles, where the Mexican Army had surrendered to Commodore Stockton and General Kearny. Upon his arrival, without authorization, Frémont negotiated and signed the Cahuenga Articles of Capitulation with Mexican General Andres Pico, effectively ending the conflict in Alta California.

Fremont was appointed military governor of the newly acquired California Territory by Commodore Stockton. However, General Kearny had orders from President Polk to serve as governor. Frémont initially refused to step down, but eventually accepted the order and was court-martialed for mutiny and insubordination.

President Polk commuted Frémont’s sentence, but Frémont nevertheless resigned his commission and returned to California, where he purchased land.

In 1849, when the gold rush hit, Frémont was fortunate to own land with gold on it and made a handsome fortune. In 1850, California was admitted to the United States, and Frémont was elected as one of the two first Senators from California. In 1856, he became the candidate for the newly formed Republican Party and was defeated by James Buchanan.

At the start of the American Civil War in 1861, Frémont was made Major General and put in charge of the Department of the West by President Lincoln. Later that same year he was relieved of duty by Lincoln for insubordination.

Frémont later served as territorial governor of Arizona from 1878-1881, before retiring to New York. He passed away in New York City in 1890.

Frémont’s march through Santa Barbara has become part of our local history and the ridge that bears his name provides an opportunity to explore first hand part of the route he covered.

This article originally appeared in Section A of the November 28th, 2016 edition of Santa Barbara News-Press.