We’re probably always surrounded by more wildlife than we actually see or notice, but somehow on Santa Cruz Island, maybe because there are less distractions, and of course plenty of foxes, it can become a little easier to see wildlife in action.

Santa Cruz Island is the largest of the four islands directly off the coast from Santa Barbara. The islands are home to more than 140 species of plants and animals found nowhere else in the world, including the island fox and Santa Cruz Island scrub jay.

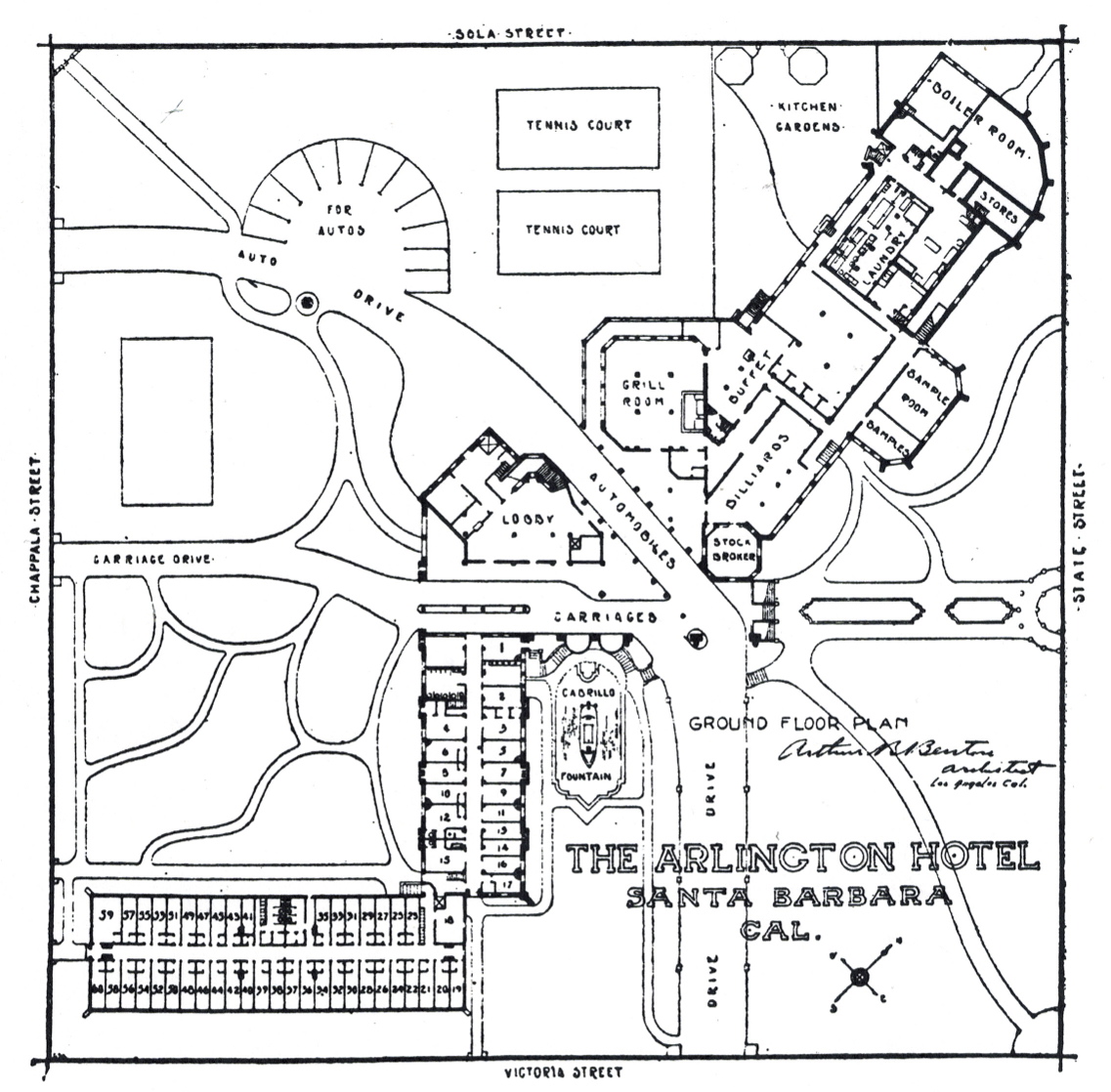

The island offers year-round camping and lends itself well to hiking with a variety of trails and old ranch roads to explore.

The easiest way to reach the island is through Island Packers out of Ventura, www.islandpackers.com, which offers regularly scheduled boat rides to all five of the islands within Channel Islands National Park.

As part of my three-day trip with friends and family, I plan to hike over towards Smugglers Cove and continue to Yellow Banks. From the campground it’s about seven miles roundtrip to Smugglers Cove and another three miles roundtrip to Yellow Banks.

A map of the trails, as well as hiking and camping information can be found on the Channel Islands National Park website, www.nps.gov/chis.

From the landing pier, we make our way past the old ranch buildings to Scorpion Campground. Both the lower and upper campgrounds are nestled under non-native eucalyptus trees that line the floor of Scorpion Canyon. The trees provide welcome shade as much of the eastern end of the island is grassland and chaparral.

As we settle into our campsite, I hear the distinctive cry of a scrub jay and spot a blue flash darting over to the next tree. A pair of Santa Cruz Island scrub jays are busy foraging on the eucalyptus trees for insects.

Island scrub jays are found only on Santa Cruz Island. They are a third larger than their mainland relative and have brighter and more vibrant coloring. Other birds that can also be observed on the island include hummingbirds, morning doves, flickers, sparrows, and house finches.

Both lower and upper campgrounds have potable water and restrooms. All of the sites have picnic tables, as well as metal storage boxes to keep food and belongings safe from inquiring ravens and foxes, which regularly visit the campgrounds.

During the orientation at the pier, the ranger cautioned us not to leave packs unattended as both ravens and foxes are keenly aware that visitors bring with them food and both are adept at opening up gear and tents and scattering the contents about.

He also emphasized the importance of not feeding foxes, as cute as they are, because it significantly undermines the foxes ability to remain wild and not become dependent on people.

The island fox is found on six of the eight Channel Islands and has made a remarkable recovery. In 1999, with dwindling numbers, a captive breeding program was started along with other measures to protect the fox. With growing success, captive breeding was ended in 2008; and in 2016, the fox was removed from the endangered species list.

On the second day, I set out for Smugglers Cove and points beyond since I have the whole day to work with. From the upper campground, the trail continues up Scorpion Canyon.

Just past the last campsite, I spot a well-worn side trail leading into the creek and decide to follow it. Across the creek from me are several large toyon bushes laden with ripe, red berries, similar to those I’ve seen elsewhere on the island.

I return to the main trail and continue up the canyon; a few moments later I hear a rustling sound behind me. Turning back, I spot a fox eating berries in the tall toyon bush I had just been standing in front of.

Returning to the creek, I watch as the fox maneuvers itself amongst the branches to get at the ripe berries. On the ground are numerous piles of fox scat, suggesting that this is a popular spot with the foxes.

Island foxes are related to grey foxes found on the mainland. The island fox is a third smaller in size; both foxes are the only North American canines that can climb. The foxes are also both omnivores. Island foxes will eat deer mice, crickets, and a variety of berries when available.

Sensing this fox might be there for a while, I continue up the canyon, passing several more foxes along the way.

The previous day I had been reflecting on the different approaches to immersing in nature. While I enjoy sitting in one place and observing what’s around me, my wanderlust often takes me on long treks where I get to see the landscape unfold and change over the course of the hike.

Both have their merits but I sometimes wonder what it would be like to spend even more time in one place. Of course, the long hike ultimately wins out, but the climbing fox just outside camp makes a compelling argument for not needing to travel far to see interesting things.

The trail continues another quarter-mile up the scenic canyon, before beginning it’s climb out of the canyon.

At about the 1.5-mile mark, the trail meets Montañon Trail. At the intersection are the remains of an old oil well.

Most of the the trail junctures on the island are well-marked. From this juncture, the trail to the right continues up towards the Montañon Ridge. To the left, it continues another half-mile, where it meets Smugglers Road, which comes up from the pier and leads over to Smugglers Cove.

Continuing towards the south shore, the road eventually crests a rise in the terrain revealing the balance of the hike. From here, I can see the trail wind its way down to Smugglers Cove. To the east, Western Anacapa Island comes into view.

As the road continues its descent it passes through a stand olive trees planted in the late 1800s.

Near the beach is a stand of eucalyptus trees, also a remnant from the ranching days. The trees provide shade for the picnic tables where there are plenty of foxes to keep me company while I stop to rest.

The tide is out and so I wander down the sandy beach to see how far I can get. At the far end, the beach becomes rocky, but as I press on I can see a way to clamber over the point and continue on to Yellow Banks.

The beach at Yellow Banks stretches out about a half-mile and unlike Smugglers Cove is covered in cobblestone. The ongoing action of the surf pushes against the stones creating essentially a long wall, which I walk along the top of.

Yellow Banks takes its name from the outcroppings of Monterey shale visible even from offshore that have a distinctive yellow color. I hike down the beach as far as the mouth of Cañada de Aguaje. On the way back I pass the same fox I’d seen earlier foraging amongst the rocks; this time it watches me as I wander by.

From the beach, I make my way up the hillside and join the long ranch road that loops back over to Smugglers Cove and continue on towards Scorpion Campground, retracing my route as the sun sets.

Even hiking in the dark is different on the island, there are no bears or mountain lions to worry about and any mysterious rustling sounds are likely from a fox.

On the last day, before returning to the mainland, I check the wildlife cameras I’d set out in the dry creek near camp. Viewing the images on my digital camera I can see where a fox has been very interested in several rocks along the side of the creek. It also looks like the motion-activated camera has taken a lot of “blank” photos, maybe from the wind moving through the brush.

Back home, viewing the images on my computer, a different story emerges. Noticing subtle changes between the “blank” photos, I zoom in to discover that the camera captured images of Santa Cruz Island deer mice.

During the night, the fox had visited the creek bed. In the exact spot where it had been sniffing around, 30 minutes later two mice pop up and boldly scamper about. The scene repeats itself several times throughout the night, with the fox unsuccessfully catching any mice.

The photos add to the sense that our islands are busy with activity, even when we’re not around or stop to notice.

This article originally appeared in section A of February 5th, 2018 edition of Santa Barbara News-Press.

A Santa Cruz Island Fox feasting on toyon berries

*

Smugglers Cove

Yellow Banks is seen in the late afternoon light

A Santa Cruz Island fox settling in for a nap

Anacapa Island frames a view overlooking Scorpion Anchorage

Western Anacapa Island is seen from Smugglers Road

A Santa Cruz Island fox watches at Yellow Banks